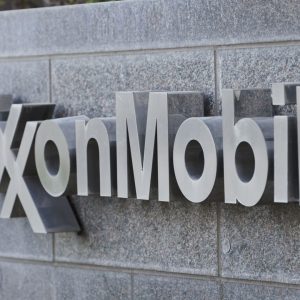

One of the many policy consequences of the 1969 Santa Barbara Oil was a strong regulator of oil drilling and transportation at the county level in Santa Barbara County. Santa Barbara County’s Planning and Development Department’s powerful Energy Division is an amazingly strong office with a suite of powerful permitting and oversight tools across oil and gas production in the county. This office directly emerged from the fallout of the 1969 spill. Moreover, the heightened concern that the 1969 spill brought to us all merged with numerous other concerns in the 1970s:

One of the many policy consequences of the 1969 Santa Barbara Oil was a strong regulator of oil drilling and transportation at the county level in Santa Barbara County. Santa Barbara County’s Planning and Development Department’s powerful Energy Division is an amazingly strong office with a suite of powerful permitting and oversight tools across oil and gas production in the county. This office directly emerged from the fallout of the 1969 spill. Moreover, the heightened concern that the 1969 spill brought to us all merged with numerous other concerns in the 1970s:

- growing awareness of the importance of the Santa Barbara Channel as an amazingly diverse migratory corridor for virtually all of the large whales that live in the eastern Pacific

- very high numbers/rate of tanker traffic in and around the Santa Barbara Channel

- the acknowledgement that pipelines (despite their known risks and the fact no transportation mode is perfect) are the safest method to move gases and liquids in the U.S.

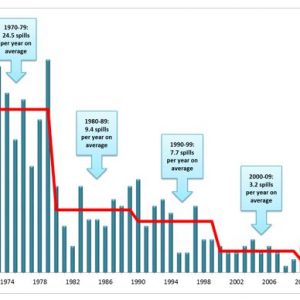

These swirling forces resulted in terrestrial pipelines being the mode of choice for the crude produced in the Santa Barbara Channel and various pipelines being created or adding on additional spurs throughout the 1980s, creating the pipeline network that we have now. This brings crude from coastal collection/distribution facilities to refineries in Santa Barbara and Kern Counties. See the map and detail below:

Oil and gas facilities across Santa Barbara (and extreme western Ventura and southern San Luis Obispo Counties). Source: Santa Barbara County Planning Division.

So our moving of crude via pipelines has reduced the risk of a maritime spill, but made us dependent on (effectively) a “single lane” highway for crude: the All American Coastal Pipeline. Obviously that is now down thanks to the May 19th break of trunk 901. In the week following the spill, an essentially identical trunk line (903) that brings crude to Kern County was deactivated over concerns that a similar break was possible given identical maintenance records, similar pipeline thinning, etc. This seems prudent given all the concerns about insufficient maintenance/oversight and all the hallmarks of what will be a huge political theater of a legal investigation. This has driven local production wells to be greatly staunched. Wellheads feeding into the Plains pipeline have been slowed to about a quarter of their normal flow rates. Currently that oil is being stored in the onshore facility (Las Flores Canyon, just to the right of the Refugio pipeline break in the above figures) very close to the break at Refugio. But even at this reduced production level, we will run out of onsite storage within 10-14 days.

This all brings us to yesterday when Exxon petitioned that ol’ Energy division at County Planning for permission to start trucking oil. And we are talking a lot of trucks. As in 192 more truck trips per day on the Gaviota stretch of the 101. As the LA Times is reporting this morning:

The company told Santa Barbara County officials Thursday that it wants to send a fleet of 5,000-gallon tanker trucks along U.S. 101 at a frequency of eight trucks per hour, 24 hours a day, every day, said Kevin Drude, the head of the county’s energy division.

“They are totally pinched off right now,” Drude said. “The only way out of the county is through that pipeline network.”

This will proceed until the pipeline can both be fixed AND certified for routine operation. The current estimate is months. Good luck with that, by the way.

Not to digress into other PIRatE Lab research, but we can add to the list of impacts from this spill all the increased road kill that will spin-up out of this increased trucking efforts. Large trucks such as these crude tankers are the least nimble vehicles out there and are much more likely to kill large wildlife. So while this may be inevitable given the options on the table, increased road-associated mortality is going to happen. This should be an additional factor in the mix added to the actual impact of this spill. My lab can actually estimate the amount of increased animal kill rates from this increased traffic…although we are still on the beach at the moment covered in tar balls. Stay tuned.

Leave a Reply