Two years ago today our field teams were assessing El Capitan State Beach as the sun rose. Pictured here are ESRM undergraduate Chase Tillman and ESRM Technician Paul Spaur on May 20, 2015.

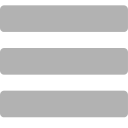

Two years ago today (about 18 hours after the initial release), our field teams were onsite at El Capitan State Beach monitoring sandy beach conditions just prior to the arrival of the spreading oil slick from the Plains All American Pipeline break’s epicenter at Refugio State Beach. We’ve learned much over the ensuing two years about the largest oil spill in Santa Barbara County since the 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill.

Dr. Anderson discussing the second anniversary of the 2015 Refugio Oil Spill from Boston Commons in Boston, Massachusetts on May 19, 2017.

Yesterday (May 19) marked the 2nd Anniversary of the Refugio Oil Spill initial release. We first got wind of the spill spill when KEYT called us up asking for some context and interpretation. Kelsey Gerckens ended up interviewing me in the parking lot of my son’s Boy Scout parking lot. Her call prompted me to activate my network of colleagues and professional contacts to start getting a handle of what was beginning to unfold around us. When the sun came up the next morning (May 20) our coastal monitoring teams were already assessing that still-open El Capitan State Beach. Lifeguards would move to start shutting down the state beach for folks other than us and evacuating campers by 7:30am. We would spend nearly everyday for the next six weeks scrambling across the beaches and nearshore waters from Refugio down through Manhattan Beach in our efforts to measure the initial impact of the spilled oil from Plains All American’s Line 901.

Kelsey Gerckens of KEYT3 News interviewing Dr. Anderson in a Ventura County parking lot on May 19, 2015.

Two years out from the spill we see most of the ecological impacts (or at least the statistically significant signal) healed and beaches that were heavily oiled are now indistinguishable from their condition pre-spill. A new study wherein we have been hunting for long-term chemical fingerprints from the spill is just ramping up but we seem to be find little evidence of remnant oil toxicity at Refugio from that 2015 spill.

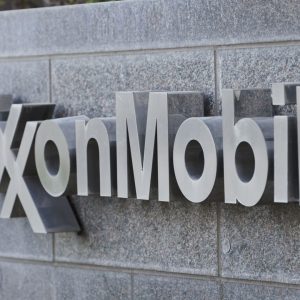

The clearest impact from the spill remains in the socio-economic realm. We saw major changes in visitor spending post-spill as people spent dramatically less money at beaches heavily oiled/tar balled in comparison to cleaner beaches. That initial economic hit for coastal businesses had abated by three months post-spill. However this past year has seen the larger regional economic ramifications only grow. Chief among this has been the several bankruptcy filings by Venoco. This culminated in their finally completely pulling the plug on their large, local oil company and all their associated operations last month on April 17. The company has already quick claimed its offshore oil platform Holly and the South Ellwood Oil Field to the California State Lands Commission and the state has begun the process of starting to permanently cap more than 31 well bores to permanently halt oil production from those reserves (little to no oil has been produced from these reserves post Refguio spill). While oil prices and the oil drilling policies along California’s South Coast strongly influenced their decision to shutter their company, the primary driver of Venoco’s insolvency was the fact that two years out Plains All American has yet to return their oil pipeline to service and therefore effectively prevented Venoco from being able to move or sell any of its oil from the Santa Barbara Channel. Environmental groups have cheered this defacto shuttering of a large number of oil wells in California State Waters (they were also buoyed by the Trump Administration’s recent pull back from efforts to open up federal waters off of California to new oil lease sales).

In terms of the regulatory environment post-Refugio, we are still struggling through the “lessons learned” process. Helmed by the Coast Guard, many of us have been involved with a post-spill assessment of our response efforts. While we have made progress on several things such as pre-approving new clean-up technologies so they can more quickly be used to respond to some future spill and streamlining and standardizing geospatial data collection and sharing, key reforms that would address the abysmal public communication and poor integration of federal-state-local-NGO-academic agencies/resources remains only in the discussion stage at this point. While this should come as no surprise, getting the bureaucracy right remain perhaps the greatest challenge and possibly the greatest self-inflicted wound. Back in the day an oil spill would lead to rapid evolution of policy and procedures to improve our response to future spills. But the political gridlock infecting much of our federal government means that we are by in large repeating mistakes and failing to learn from the past.

Leave a Reply