The BM Maple that collided with the Dawn Kanchipuram outside Kamarajar Port. Image: Times of India/C. Suresh Kumar.

Our friends in India are battling a new oil spill that began in the early morning hours of Saturday, January 28, 2017. The cargo ships BM Maple (UK flagged) and Dawn Kanchipuram (Indian flagged) collided about 4 km outside the mouth of Kamrajar Harbor, itself about 24 km north of Chennai Port, Chennai in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The Dawn Kanchipuram‘s fuel and/or storage tanks (it is still a bit unclear from news reports at this point during this unfolding event) ruptured in the crash, spilling a reported 317,400 bbls (9,900,000 gallons, 37,250,000 liters, or 32,813 tons) of oil into the coastal waters in this western swath of the Bay of Bengal. BM Maple was apparently empty/unladen. Port officials failed to notice anything was amiss until they noticed oil on the water’s surface that evening. Even so, officials apparently thought it was a minor leak from one of the ships, said Atulya Mishra Tamil Nadu’s environment secretary. Clearly the notification system and activation mechanisms for their formal spill response network is wanting. By Sunday the oil was making landfall, initially collecting in the fishing village Radhakrishna Nagar Mr. Mishra said. That appears to have helped trigger the larger scale response that is now in full effect one week post-spill.

Response has been a bit opaque to date with authorities taking at least 30 hours to tow the leaking vessel into port, but the Indian Coast Guard is helming response efforts and has detained the crews of both ships pending deeper investigation. Clean-up was well underway within a few days of the release and now includes at least 1,200 people from a variety of organizations; Kamarajar and Chennai Ports, the Tamil Nadu state agencies, Indian Oil Corporation, various NGOs, cadets/students from maritime academies, and local fishermen. Specifics are slow to emerge a week later but the seas must have been fairly calm given the clean-up has involved three oil-collecting vacuum platforms (deemed “super suckers” in the Indian Press) in recent days, collectively removing a mere 9,000 liters (2,380 gallons or 56 bbls) of oil as of the last updates. Dispersants are being deployed by the Coast Guard with at least 2,000 liters (528 gallons) being sprayed from surface ships proximate to the Chennai Lighthouse. At least “four tons” (roughly 1,000 gallons or 3,800 liters) of dispersants have been deployed from helicopters and surface ships overall as of February 1st.

Coast Guard officials seemed to initially downplay the magnitude of the spill saying February 1st that roughly:

“95% of the oil slick is towards the northern side of Chennai Harbour. Oil sludge has accumulated over a length of 800m spread across 11 spots north of Chennai port.” The Marina shore suffered minimum impact and would supposedly be cleaned by February 1. “At the shoreline around Tiruvallur, oil has accumulated over a 2-3km stretch of shoreline. Here also the impact was minimal. We will clean up this area after attending to more seriously affected parts in the north of Chennai.”

As our lab knows too well, such proclamations often wildly overreport or underreport impacts in the early days, especially when the folks doing the reporting have limited experience with oil spills, ecotoxicology, or environmental impact assessment. Describing the impact of something on the order of magnitude of 300,000 bbls as “minimal” is perhaps overly optimistic. Of course time–and actual data–will tell.

Coastal clean-up near Chennai, India. Image: India Live Today.

Widespread oiling of of beaches in the region has followed in the wake of the spill. As the clean-up has hit full stride 30 tons of oil sludge and 11 tons of mixed oily sand was removed from the the beaches and intertidal of Chennai, Tiruvallur and Kancheepuram Districts on February 5th. That single day harvest raised the total oil recovered to date to 121 tons (roughly 136,000 liters or 36,000 gallons) of sludge, 65 tons (74,000 liters or 19,500 gallons) of oily sand and 72,000 liters (19,000 gallons) mixed oil and water, according to a press release from the Coast Guard. Setting aside the fact that much of these reported numbers for recovered materials are non-oil substances (sand, seawater, etc.) workers have recovered less than 1% of the reportedly spilled petroleum. Disappointing to say the least, but not uncommon for a spill that began so far out to see and had such a slow ramp-up phase. Puzzlingly, The Hindu reported yesterday that “At Neelankarai, sources said that some persons, who had cleared the beach yesterday, had buried the tar forcing volunteers to dig up the top soil at several locations.”

No clear reliable estimates of impacts to organisms have come in yet, but concern has been voiced over the usual charismatic megafauna that appears to be a mandatory part of any oil spill reporting endeavor. In this case, the “poster child” critter is the olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) that has nested on Chennai’s sandy beaches for millennia (and monitored for the past 40 years), said Mr. V. Arun, coordinator of the Students’ Sea Turtle Conservation Network. Ridley’s are listed as a vulnerable species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Arun said he had seen turtles and crabs “smothered by oil” on the shore near Chennai. Olive ridley turtles are potentially a particularly sensitive species to spills such as this given their natural history which includes large groups of turtles gathering offshore of nesting beaches before landing en masse (hundreds to thousand of females) in so-called arribadas for a synchronous, nighttime laying of eggs in the sands of the upper swath zone on sandy beaches. Their numbers can be so high at optimal beaches that previously-laid egg clutches are sometimes unintentionally dug up by other females excavating their own nest. Sea turtle numbers worldwide are in decline. Unfortunately January to April is the peak beach nesting period in this region of India. Students Sea Turtle Conservation Network volunteer Shravan Krishnan reported to The Hindu last week:

For turtles which are nesting, they will find it tough to come on to the sand since oil sediments are there till the high tide line in a few spots. While volunteers who patrol the beaches from Neelankarai to Besant Nagar near the broken bridge usually spot a lot of crabs during the patrolling in the night, they were hardly able to spot a few ones last night and even those were seen with oil on them. In the coming days, we will have to observe if there is a large impact on nesting activity as this is an important time in the annual nesting season.

Chennai: January 31, 2017. Initial evidence of several dead turtles and fish are evidenced by this shot of an old beach and dead turtle on or near Thiruvanmiyur Beach, India. Image: The Hindu/M. Karunakaran.

Spills like this event which oil large swaths of the littoral zone harm developing eggs or just-hatched juveniles are but one additional challenge adding to the already daunting threats of habitat destruction, over harvesting, etc. Poorly trained clean-up crews also can easily crush/kill eggs in the nest during response efforts on impacted beaches.

Chennai Students’ Sea Turtle Conservation Network volunteers taking measurements of a nesting female on a Chennai beach. This and previous image: SSTCN.

Mr. M. D. Dayalan, president of the Chennai-based Indian Fishermen’s Association, said many of the estimated 100,000 fishermen in villages along the coast have had to leave the area. Few details of this story are in the English-language press at this point, but this could well become a key part of this spill’s legacy.

Significant floating oil along the shore of north Chennai came as a shock to the fishing villages, given the Port authorities had said on Saturday that there was only a thin sheen from the ships, it would disappear soon, and there was no reason for concern of greater impact. Image: The Hindu/R. Ravindran

This video is pretty good and includes some drone footage of the spill, but won’t embed properly and I have therefore included it only as hyperlink for anyone interested.

As you would expect, we are seeing the usual concern over the lack of media attention and worries about potential impact to the coastal environment and fishing communities on social media:

The oil spill in Ennore,Chennai will have worst environmental impact. No media coverage till now. #ChennaiOilSpill

— Ashwin (@Ashwin_0291) February 1, 2017

#EnnoreBeach Chennai, scary oil spill. Negligence will harm marine life and affect fishermen’s livelihood.

— Gita S. Kapoor (@GitaSKapoor) February 2, 2017

National new channels just now discovering the oil spill in Chennai and calling it exclusive. Pathetic! Tyranny of distance from Lutyens! https://t.co/gdzLDwS54W

— Mahesh (@invest_mutual) February 2, 2017

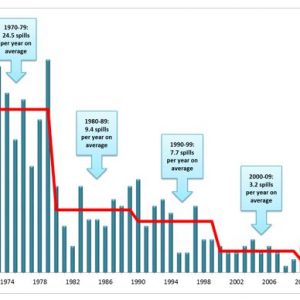

Finally, by way of context, recent oil spills in India have included:

- In October 2013, a pipeline in the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation’s Uran plant developed a small leak ultimately spilling about 5,000 liters (1,300 gallons or 31 bbls) of crude oil into the Arabian Sea that spread about 10 km along the coastline. See a nice piece of the growing threat of pollution to fishermen around Mubai in the New York Times from 2013.

- In August 2010, the collision of merchant ships MSC Chitra and MV Khalija 3 off Mumbai’s coast spilled >900,000 liters (240,000 gallons or 6,000 bbls) of oil into the sea. As a result, a huge swath of mangroves along the coastlines of Mumbai, Thane and Raigad districts were severely degraded.

- In January 2011, the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation’s Mumbai-Uran oil pipeline burst spilling an unknown amount of oil across 4 km2 off the Mumbai coast. Later in August of 2011, the MV Rak carrying 60,000 tons of coal, 290 tons (330,000 liters, 87,000 gallons, or 2,100 bbls) of furnace oil and 50 tons (56,000 liters, 15,000 gallons, or 360 bbls) of fuel oil, sank off the coast of Mumbai releasing its fossil fuels into the sea.

Leave a Reply