It is almost one month since our most recent energy infrastructure foundering: Crimson Pipeline’s release of crude oil into the hills above the City of Ventura. Lots of developments continue to burble up as we all try to figure out the next surprise.

It is almost one month since our most recent energy infrastructure foundering: Crimson Pipeline’s release of crude oil into the hills above the City of Ventura. Lots of developments continue to burble up as we all try to figure out the next surprise.

As we assessed the spill in the immediate wake of that June 23rd release, I predicted this comparatively small volume of oil would be one of the easiest clean-up processes, happen very quickly (with primary recovery possibly needing only a few weeks), and translate into a superfast, straight-forward mitigation period. Just goes to show what I knew. While certainly not the end of the world, the last few weeks have been disappointing on many fronts. Some of these happenings are a consequence of particulars of the site and spill, but most seem to have stemmed from our expansive spill response bureaucracy and the lack of information/clarity from the responsible parties.

More Oil Than First Reported

The mantras that I often push on my undergrads studying unfolding disasters are being borne out even in this small, contained spill:

- “Never trust the first numbers.”

and

- “Spillers minimize, enviros maximize, and our agencies are too understaffed and hampered by procedural weight to provide their own robust, independent numbers.”

The modern pattern we tend to see with everything from estimates of those killed in mass casualty events to the volume of pollution loosed into a waterway is inaccurate first appraisal. This phenomenon of inaccurate initial estimates appears to have intensified in our era of “numbers now.” Our instant social media and 24-hour news cycle increasingly prizes speed over accuracy and fosters an ever-larger and ever-louder megaphone amplifying whosever sub-optimal numbers are first into the slipstream. The anchor for a respected national news outlet interviewing a reporter at the scene of a breaking news event yesterday morning went so far as to say, “I understand that nothing is confirmed and the scene is chaotic, but can you give me any kind of number?” The beast must be fed apparently.

Add to this pressure for “numbers now” the inherent tendency of polluters (aka “responsible parties” in the parlance of our current environmental policy) to lowball the size of the release, environmentalists to overestimate the size, and regulators to simply parrot one or the other in the early hours and days. We are left with the situation where our final estimates of spilled oil nearly always differ substantially (often orders of magnitude) from the widely quoted initial estimates, regardless of the particulars of the spill in question.

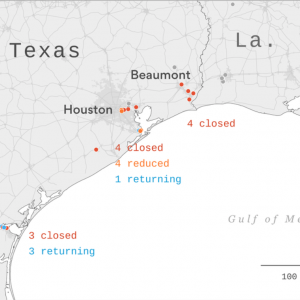

Cal Spill Watch on July 9, 2016.

Usually any such revision to volume released is made quietly and garners scant if any media attention. In the case of the Hall Canyon Spill (also referred to as the Groves Incident), estimates were revised upward and motivated coverage in the Ventura County Star a week ago. On July 8, Cal Spill Watch (the oil spill information page for the state of California’s Office of Office of Spill Prevention and Response) posted an upward revision to 171,000 l (45,000 gal, 1,075 bbls). This updated estimate came from Crimson Pipeline and was apparently revised thanks to the large volume of recovered oil tallied by the clean-up crews. This new estimate is 54% greater than that original estimate (although inline with my own higher end estimate from my visual inspection the morning of the spill), to date still widely reported as the older “almost 29,000 gallons” number.

Revised Hall Canyon Oil Spill Estimates

| source | liters | gallons | barrels |

|---|---|---|---|

| My Iniital Estimate: High (June 23, 2016) | 190,785 | 50,400 | 1,200 |

| My Iniital Estimate: Low (June 23, 2016) | 63,595 | 16,800 | 400 |

| Official Estimate: June 23, 2016 | 111,291 | 29,400 | 700 |

| Official Estimate: July 8, 2016 | 170,911 | 45,150 | 1,075 |

A Sense of Deception

Another depressingly common phenomenon in the wake of oil spills in our modern era is the nagging sense of not being told everything. Residents proximate to the spill feel this, the general public feels this, reporters feel this, scientists feel this, and often agencies or even the responsible party feel this. In short, the structures and procedures we have erected around such events are problematic. They have emerged from our overly litigious approach to dealing with impact assessment. The focus all too often is on assigning blame and seeking (or refuting) fiscal damages rather than on fully informing the general public or scientific community who clamor for answers.

Having been involved in such events for many years, I can tell you everyone I have encountered wants to clean up and quickly mitigate any and all spill damages, but a huge amount of distrust and so-called recreancy exists between various camps and further adds to the bureaucratic layers. Case in point, the clean-up itself. . .

A Slooooow Clean-Up

Given that the oil spilled was limited to the very bottom of the Prince Barranca, it should have been easy to clean-up. Surface pooled oil was primarily suctioned up over the course of the first two days. As the creek bed was dry before the spill and the contamination was fairly constrained (generally 1-2 meters in width and perhaps 30 cm deep on average) over the course of the not quite three-quarters of a mile stretch of contaminated creek, it should have been easy to proceed to the next step of digging up and carting away all contaminated materials. This would have set-up the subsequent restoration efforts.

But one month out somewhere between 100 and 200 hazmat personnel from two different contractors are still engaged in a variety of pre-digging activities, only getting to the actual physical excavation over the past several days. Most surprising to me was the use of aggressive flushing of the creek with large volumes of potable water (up to 40,000 gallons a day) dumped into the gorge. The idea here was to try to remobilize oil retained in various pockets across the length of the barranca.

The decision to flush seems to have at least partly been motivated by concerns over trying to minimize the need to disturb soils that might harbor Native American artifacts. Additional concerns were voiced by agency personnel about the installation of steps down the ivy-covered hillsides of the barranca. We are therefore at best many weeks from cleaning up this site. All the while, mobile wildlife are potentially exposed to remnant oil, likely attracted into this once dry, now wet barranca that serves as a wildlife corridor (agency officials are monitoring the area intensely now). We are also risking wider vegetation impacts, as this oil sits and saturates into soils along the creek bank. Again, much of this is hard to estimate from outside the incident command given the lack of information coming out about the efforts within the barranca. And so this takes us to our next development. . .the PR story.

How to not get your story out

The first big PR “open mouth, insert foot” move of this spill occurred at the Ventura Town Hall just after the spill. A meeting was called on the low down by Crimson Pipeline. In truth this was not directed at nor advertised to the wider public. Rather it was an effort by Crimson to answer questions of residence in the immediate vicinity of the spill and make sure they had access to claims paperwork and points of contact of filing. What ended up taking place however was a PR nightmare for the company. It appears that they only sent representatives who knew about the claims process. Consequently when the audience (including Ventura County Supervisor Steve Bennet) asked questions pertaining to the material aspects of the spill such as expected duration of the clean-up, air quality measurements, pipeline repair progress, etc. the representatives appear to have not been fully briefed as one would have hoped. Amongst other things they failed to mention, the pipeline’s faulty junction/value that was at the epicenter of the spill was already repaired and mere hours away from being recharged with oil and returning to routine operation. I think it is fair to say that was not the best move when one is seeking to calm a nervous audience.

This and similar such opacity when it comes to finding concrete facts about the repair and clean-up have pushed Crimson into something of a defensive position to the point where they have begun turning to Op-Eds and Press releases to get their story out there. This culminated most recently in yesterday’s “dueling” op-eds in the Ventura County Star wherein Supervisor Bennett aired his concerns and Crimson Pipeline President Larry Alexander argued the case for the company in the midst of what he called “misperceptions” in the media and general public.

Amidst all this, I can see how some folks are left confused and wondering what is going on. Indeed, I feel like that most days! For now, all we can do is stay tuned and hope for an increased rate of clean up (and much less potable water being dumped down the drain).

Leave a Reply