Gabriel Anderson, 13, photographs a section of the oil spill in Ventura. He was with his father, Sean Anderson, a professor at Cal State Channel Islands, who was collecting samples to test for toxicity. Image: Mel Melcon, Los Angeles Times.

Yet another start of the summer and yet another pipeline break on the south coast.

A Year of Spilling Dangerously

Our oil infrastructure here in coastal southern California has certainly had a pretty horrid year. We started with last year’s mid-May Refugio Oil Spill. The largest oil spill in Santa Barbara County since the infamous 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill just kept on giving and giving in the form of sporadic tar balling of beaches across 170 km of coast into late June of 2015. As a consequence, my students, colleagues, and I spent the late spring and early summer of 2015 tracking tarring impacts across more than 50 of our southland beaches.

Just when we felt we had wrapped up our initial characterization of Refugio impacts, we were thrust into the Aliso Canyon Natural Gas Storage Field Blowout. That four month-long fiasco in Porter Ranch totally eradicated more than a year’s worth of very hard-won, state-wide carbon emission reductions as we vented more than 97,100 metric tons of methane and 7,300 metric tons of ethane into our atmosphere. That day in, day out natural gas blowout à la the Deepwater Horizon was caused by infrastructure that predated our energy crises of the 1970s. That venting and the ensuing management crisis hobbled our nation’s fifth largest natural gas storage facility as it burped out a carbon footprint larger than the Deepwater Horizon blowout in 2010. Both a healthy dose of prudence and a spate of legislative constraints placed on the storage facility’s owners (Southern California Gas), have kept this key piece of our energy infrastructure hobbled and offline as we enter the time of the year when we most need a nimble and quickly-responsive electrical grid (did I mention we have been seeing triple digit temperatures of late). So I hope you can forgive me for thinking we were justified in expecting something of a reprieve of energy infrastructure crises as we rolled into the 4th of July holiday.

Unfortunately, we picked the wrong week to catch up on our sleep.

Hall Canyon Pipeline Spill

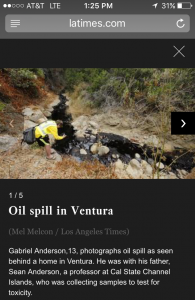

First map identifying spill site. Image: VCFD via @avmartinez

Kirk and Kelly Atwater and some of their neighbors woke to what they later recognized was likely a pressure release valve screaming an unusual whine around 4:30 am on Thursday, June 23, 2016. The Atwaters fell back to sleep, but were soon re-awoken by the pungent smell of oil wafting into their home. The increasingly strong smell eventually prodded them to walk out of their Ventura Hills home and search for the culprit. Kirk disappointedly found fresh crude flowing though a narrow creek that bisects his property above Ventura High School around 5:00 am. He hopped onto his Vespa and motored up to the oil pipeline a few hundred meters up the canyon from his home. Sure enough, the crude was pouring out of a junction box and flowing into the head of the Prince Barranca within Hall Canyon. Kirk first called 911 to alert the authorities and then called the “in case of emergency” 1-800 number affixed to the pipeline itself, reaching the pipeline’s operation control center in Long Beach, California. It was 5:30 am.

Rapid Response

The rest of us woke to news reports of a potentially very large pipeline break just east of the City of Ventura. Those first few dribbles of news suggested that as much as 200,000 barrels of oil might have been released into a creek and were apparently headed to the Ocean with a possible entry point near San Jon Road on San Buenaventura State Beach, one of our long-term sandy beach monitoring sites. It goes without saying that oil spills rarely fall on convenient days or happen at civilized times.

The previous evening saw our Sandy Beach Field Crew present the interim results of our 2016 Sandy Beach Rapid Assessment Synoptic Surveys of beach health and our assessments of Refugio Oil Spill impacts as of one year post-spill. We had just sent everyone off for some well-deserved vacation time when BANG! New Spill. Fearing several of our monitoring sites were about to (again) be hit by oil, I began reaching out to our just-deactivated field team. Several folks reported they could help, but would need a few hours to get back to town/finish-up long-postponed activities planned for that June 23rd morning. Not wanting to wait, I grabbed my son (a seasoned beach monitor, excellent parasite dissector, etc.) and we bee-lined to the City of Ventura. On our drive into Ventura, reports started trickling in that the oil appeared contained to the hillside region of Ventura near Grove Street and Grove Lane. We therefore elected to first check the origin site to confirm that oil was indeed contained near the release site.

We began by conducting a few driving transects from the 101 Freeway (near the beach) inland towards the hills on South Seaward Avenue and associated streets. Driving slowly with our windows down (and with frequent roadside pit stops), we could detect no petroleum odor as had been rumored to proximate to South Seaward Avenue. To be sure this was a qualitative assessment. But as we have seen in the past, were oil to get into storm drains or urban creeks you can rapidly see a progression of both petroleum and smells across the urban/coastal plain as those hydrocarbons migrate seaward through the urban matrix.

Following that brief odor inspection, we headed up into the hills above Ventura High School to get a firsthand read on the spill and figure out if we indeed needed to prioritize additional pre-oiling beach surveys.

A Fouled Barranca

As we approached the Grove Lane area of the Ventura Hills, we quickly honed in on the cluster of fire, hazmat, and police just off Poli Street. As our goal was to not get in the way of any first responders, we went a bit farther up the hill from the primary aggregation to see if we might be able to get a sense of the magnitude of the release in this residential neighborhood. Within a minute or so we came upon a cluster of media disembarking from their TV vans, etc. along with a scattering of County Fire in the side yard of the Kelly and Kirk Atwater. We introduced ourselves and the Atwaters kindly invited us to come on in and take a look at the spill running through the steep ravine that bisects their property. After several minutes of answering the Atwaters’ questions, we headed down for an initial inspection.

With a friendly “be careful of the poison oak, its really thick down there,” we shimmied down the ivy-covered bank to where a few intrepid news photographers and videographers were collecting images of flowing oil in the small channel for their upcoming stories.

The pipeline release point was perhaps 500 m upstream from our inspection site on the Atwater Property. The Prince Barranca lies within the greater Hall Canyon and is a key tributary for local surface water migrating from the upper reaches of this section of the Ventura Hills down to the flatlands of the core of the City of Ventura and eventually into the arroyo that discharges into the ocean at San Buenaventura State Beach (one of our beach health monitoring sites) at San Jon Road. At the Atwater’s home, the rim of the gorge is spanned by a city water main essentially running straight across the perhaps 200 m span of the top of the channel, suspended perhaps 50 m above the floor of the barranca. The barranca’s sides run downward at slopes of 20 to 40° which made access a challenge for clean-up crews (later in the day they would cut steps into the slope’s face to make it easier to ascend and descend with equipment). Oil was flowing in the primary channel such that at peak the torrent averaged about 30 cm in depth (excluding pools) and one to two meters in width.

From afar I initially mistook this flow to be oil being discharged into a low flow channel capturing surface runoff. As I got closer it became clear that there was no water in this channel and I was seeing pure crude running through an otherwise dry channel.

About 400 m down stream from our inspection point, hazmat teams managed to bolster the berm surrounding a pre-existing debris basin at the end of the daylit segment of this channel before it runs under the core of city streets. Hazmat pumps and tankers were joined by at least two 3,000 gallon tanker trucks from the clean-up contractors by about 9:30 am. Major oil flows in the channel had effectively ceased sometime before 9:15 am.

Pumping oil from catchment below Atwater property ~9:00 am. Image: @VCFD_PIO

By 10:00 am the oil level in the barranca at the Atwater property had dropped perhaps 10 cm (4 inches) and perhaps 20 cm (8 inches) by 10:30 am from the maximum oil level. From my quick inspection there seemed to be comparatively little soil penetration given the density of both river stone and the thick natural cementing of the sediments in the thalweg. The pumping out of oil from that debris basin seemed to be the primary driver of the quick draw down of the oil level.

Crew members work to keep crude oil from flowing into the ocean after a spill in Ventura, CA. Thursday, June 23, 2016. Image: Rob Varela / The Ventura County Star.

Spilled Crude

This oil was a light crude that exhibited surprisingly little volatilization. The heavy marine layer/June gloom clearly helped with that, but the lack of strong odors (confirmed by VOC sniffers in use by the firefighters distributed across the neighborhood) was still something of a mystery. We collected a few samples of the clean crude for subsequent toxicity experiments and (if needed) fingerprinting. This crude was extracted from backcountry wells elsewhere in Ventura County by Aera Energy.

Our most recent estimate of total oil released has not been updated since early afternoon on June 23. We know these numbers are often subject to revision (usually quietly, with little public attention), but for now our official estimate is pegged at 700 bbl (29,400 gal, 111,290 l). While this was an “up to 700 barrels” number in the words of the official press release from unified command, that seems within the ballpark of what I was seeing in the channel and debris basin. Look for a revised number when the clean-up crews wrap their operations.

Wildlife Impacts

Residents reported that this barranca is dry save for in the immediate wake of our very infrequent heavy rainfall. They couldn’t recall the last time the channel harbored significant flow, but it has clearly been at least several years. Desiccated and decayed algal thalli (presumably Cladophra spp.) in the channel substrate suggest that even the routine bankside irrigation by residents wasn’t enough to support significant algal or invertebrate communities. While I expect these organisms were more abundant in the deeper pools, those were totally obliterated by the crude oil and not assessable during my brief, post-oiling assessment.

A pair of Cooper’s Hawks (Accipiter cooperii) had recently taken up residence adjacent to this stream, hitting the local Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) populations hard. Other birds that were common include the usual suspects osuch as Buteo hawks and corvids. I saw no evidence of vertebrates coming into contact with the oil as of mid morning.

Archiving field samples in our lab. This crude was collected flowing in Prince Barranca. June 23, 2016.

The likeliest longer term impact of this spill will be to vertebrate movement. This barranca is clearly a wildlife corridor facilitating movement of small to medium terrestrial vertebrates (e.g. skunks, bobcats, coyotes) through this neighborhood. Oil and a lack of soft sediments made detecting any tracks or sign difficult, but the landscape strongly suggests such use (an observation later confirmed by local residents). It would be great to set-up a few camera traps in the ensuing weeks post clean-up to confirm such wildlife use as our lab has done elsewhere in the county.

Crimson Pipeline

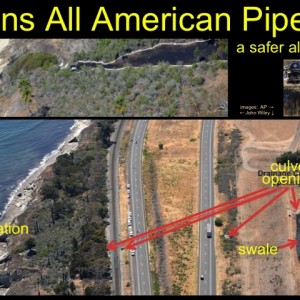

Initial reports have now confirmed that a pipeline junction experienced some type of catastrophic failure rather than a corrosion-driven failure of the pipe walls per se as we saw with Plains All American’s Line 901 segment in Santa Barbara County that birthed the Refugio Spill in May of 2015. Oil was flowing from the 25 cm (10”) diameter V-10 pipeline that carries crude from inland production fields in Ventura County to Los Angeles refineries. V-10 is owned and operated by Colorado-based Crimson Pipeline LLC. As with so much of our oil and gas infrastructure, this pipeline is old. Company spokeswoman Kendall Klinger reported that while V-10 was built in 1941, it was well maintained, current with all relevant safety inspections, and has been actively maintained. Indeed, residents in the Hall Canyon area noted that workers we conducting repairs late into the night (to at least 10:30 pm, using high-output lighting arrays to illuminate their worksite) the evening before the spill. They were apparently working on that exact segment of pipe that failed and began disgorging oil hours later and subsequently referenced by Ms. Klinger.

Paralleling the Refugio catastrophe, suboptimal detection systems may have been a key point of failure. Pipeline spokeswoman Kendall Klingler subsequently reported V-10 had been emptied of oil earlier in the week for maintenance work, then subsequently re-charged with oil post-servicing (apparently the previous night). She suggested that the system was not fully pressurized at the time of the spill and that this lower than normal operating pressure of the line prevented the usual spill detection systems from working.

In the wake of this spill, several news outlets have noted that Crimson has a history of petroleum releases in recent years.

Crimson Pipeline Previous Spill History

| Date | City | County | Cause | Initial Cost | oil spilled (l) | oil spilled (gal) | oil spilled (bbls) | net oil lost (l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11/20/2006 | Long Beach | Los Angeles | Corrosion | $100,060 | 318 | 84 | 2 | 159 |

| 4/24/2008 | Ventura | Ventura | Failed Seal/Pump Packing | $654,300 | 1,061,876 | 280,518 | 6,679 | 0 |

| 12/9/2009 | Ventura | Ventura | Equipment Failure | $10,347 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7/1/2011 | Huntington Beach | Orange | Corrosion | $911,000 | 3,179 | 840 | 20 | 795 |

| 8/17/2011 | Fullerton | Orange | Excavation Damage (3rd Party) | $49,800 | 318 | 84 | 2 | 318 |

| 9/8/2013 | Los Angeles | Los Angeles | Electrical Arc (from 3rd Party) | $3,107,125 | 1,590 | 420 | 10 | 795 |

| 10/6/2013 | Ventura | Ventura | Equipment Failure | $190,000 | 79,494 | 21,000 | 500 | 1,590 |

| 11/12/2014 | Long Beach | Los Angeles | Corrosion | $285,500 | 795 | 210 | 5 | 477 |

| 9/21/2015 | Camarillo | Ventura | Corrosion | $41,675 | 3,816 | 1008 | 24 | 0 |

| 12/8/2015 | Somis | Ventura | Excavation Damage (3rd Party) | $525,700 | 33,546 | 8,862 | 211 | 159 |

The federal Department of Transportation’s Pipeline & Hazardous Materials Safety Administration’s pipeline incident database shows Crimson’s California pipelines were responsible for 10 other spills (as of May 1, 2016) caused by corrosion, equipment failure, and other actors damaging their pipes since 2006. Half of these happened in Ventura County. The estimated 1,185,000 l (7,453 bbls, 313,000 gal) of petroleum released caused at least $5.8 million in property damage. It should be noted that nearly all the oil released from these spills was recovered during remediation efforts, that the median oil released per spill was 2,385 l with a mean release of 118,493 l per spill, and apparently one-third of these spills were caused by outside parties’ actions (when other entities were conducted excavation operations nearby a given oil pipeline segment, etc.). Lastly, it is important to keep in mind that the requirements for reporting any such spills have been tightened up in recent years and now include reporting what had historically been considered a negligible (non-reportable amounts) release.

Crews will need several more days of clean-up to harvest the last of the contaminated soils and associated materials. Restoration will, of course, be a longer-term game.

Helping the Public Understand

Here are a few of the stories that featured our lab or used our lab on background in the wake of this spill:

Area Expert Speaks on Spill: Ventura County Star

Response to Incident: Ventura County Star

Ventura Spill Controlled: Ventura County Star

Spill Misses Ocean: Los Angeles Times

The Latest Spill Updates: ABC News

California Oil Spilled Near Pipeline: AP Wire Service

[…] make a difference when it comes to the initial response to an oil spill (see our work on the 2016 Hall Canyon and 2015 Refugio Spills for example). Small, conventional camera-equipped, entry-level drones can […]

[…] when it comes the initial response to a disaster (see our work on the 2017 Thomas Fire, 2016 Hall Canyon oil spill, and 2015 Refugio oil spill for examples). Small, conventional camera-equipped, […]

[…] when it comes the initial response to a disaster (see our work on the 2017 Thomas Fire, 2016 Hall Canyon oil spill, and 2015 Refugio oil spill for examples). Small, conventional camera-equipped, […]