When we see videos like this from the Coast Guard:

It is easy to take away the impression that things are all good with regards to formal response to this (or any) oil spill. The reality is these clean-up things are vastly complex endeavors, complicated by numerous laws and guidelines and overlapping responsibilities or jurisdictions. All are put into place for good reasons, but the cumulative effect can be molasses and a bureaucratic hole (try to find any specific data or information on their website for example). We are far from the worst case situation and most of the folks in the Incident Command are great people and doing everything they can to respond in an effective and efficient manner. But even in the best of times bureaucratic holes erupt. We have been trying to access to the spill site to see if our robotic units might prove a useful tool with which to characterize oiling.

Pacific Standard’s Francie Diep did a good job capturing a bit of the frustration some of us feel as we try to navigate the necessary hurdles of getting access to the site without interfering in clean-up efforts or causing a problem for responders. See her full story here, excerpts are below:

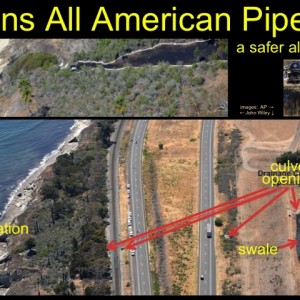

Typically, after an oil spill, seafloor assessment and clean-up isn’t part of the plan. Maybe it should be, some scientists now argue, particularly in Santa Barbara. Yet non-profits’ and universities’ requests to survey the ocean floor around Refugio have so far been rebuffed, revealing a confused bureaucracy around the official clean-up effort.

“Knowing earlier if there was subsurface oil, we could have the chance to mobilize the kind of clean-up technology we wouldn’t use normally,” says Sean Anderson, an environmental researcher at California State University Channel Islands who also studied the Deepwater Horizon spill. “I think it should be a part of oil spill assessment.” It’s difficult to lift oil up from the bottom of the ocean, Anderson acknowledges, but clean-up crews could leave containment booms around the surface of the water above a pocket of seafloor oil, to gather the stuff in case it gets stirred up. If there is oil in the bottom of the Pacific that officials are unaware of, it may wash up later, requiring clean-up crews—and all their equipment—to return once again. Resurfaced oil may even make people think there’s a second spill, requiring costly testing of the oil, to check its source…

…Meanwhile, no one has yet been able to get permission to survey the seafloor. Just east of Refugio—along an undeveloped stretch of shore where actor Brad Pitt owns a house—armed wardens from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife told Pitterle to turn his boat around. The exchange was calm and friendly, but time-consuming: The wardens took 40 minutes to confirm we weren’t allowed in. Ironically, just an hour before, Pitterle had idled the boat for about 45 minutes to sit in on a conference call that authorities held for non-profits like Channelkeeper. During the call, top officials from Unified Command—the group in charge of the clean-up, which includes state and national agencies and Plains All American Pipeline, the company that owns the burst pipe—said they wanted to work with non-profits, Pitterle says.

“What we were hearing, at least from the top of the command chain, is that they’re trying to move in that direction of coordination and collaboration,” he says. “I guess it was clear when we got there that it hadn’t trickled down the command chain yet.”…

…Anderson is cheerier about the situation. “I understand there’s 3,000 things going on in everyone’s mind right now,” he says, “so we’re still pushing.” He notes that he hasn’t had trouble conducting research this week on beaches besides Refugio. But experts don’t believe there will be much oil on the seafloor outside of Refugio.

Meanwhile, seafloor sampling was an historically difficult and expensive process, which explains why it has never been a standard part of clean-up plans despite its importance. Perhaps, Anderson muses, that’s why authorities weren’t sure how to deal with his request.

But things are different now, he argues. “It’s now to the point where this is cheap and we can train someone, not in an afternoon, but in the course of a day or a couple days. It need not be an insanely expensive thing where someone needs to be paid $300 an hour,” Anderson says. “In this age of technology, one thing I think should be changing is how we respond to oil spills.”

Thick oil in the water off of the Gaviota Coast. There are natural oil seeps offshore of Santa Barbara County, so it can be hard to tell if oil in the water here is from the seeps or from last week’s spill. Santa Barbara Channelkeeper staff say this amount of natural oil would be rare for this area. Photo: Francie Diep/Pacific Standard.

Source: A Struggle to Check the Seafloor Around California’s Oil Spill – Pacific Standard

You might also be interested in our Google Hangout with our colleague Eric up at OpenROV: Examining the Impacts of the Oil Spill at Refugio State Beach (OpenROV Explorer’s Google Hangout, from May 26, 2015). You can jump to around 15:30 to hear where we talk about trying to monitor subsurface oil.

Leave a Reply